The rough-cut tool behind the cleanest riffs

In the late 1940s, in a Fullerton, California, workshop, it first appeared. Leo Fender lacked guitar ability. He was a practical thinker and radio repairman with little tolerance for musical magic. He sought an instrument able to be mass-produced, simple to repair, and capable of withstanding road and stage demands. Born in 1950, the Broadcaster was first known as the Telecaster following a legal dispute with Gretsch. What was most important was clarity not the name. This instrument did not purr nor entice. It started to speak. Sharp, clear, occasionally disrespectful.

The Telecaster was the first solid-body electric guitar that was very popular. Not because it was flashy but because it worked, it was the model for everything that came after. Two pickups. A single ash slab. A simple control plate and bolt-on neck. That was all. Simple. No profiles. Just genuine sound and immediate assault. Country pickers adored it. Blues players found its bite. Rock musicians found its punch. It didn’t set any genre. It crossed them.

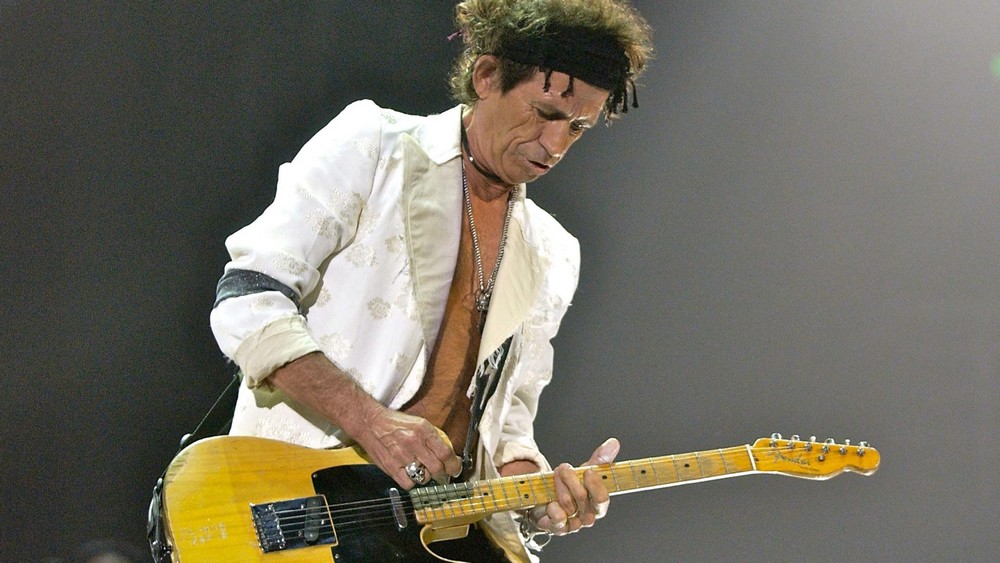

James Burton snapped it behind Elvis and Ricky Nelson. Muddy Waters roared it in Chicago. Buck Owens and Don Rich made it sparkle from Bakersfield. With Start Me Up, Keith Richards converted it into a riff machine; Bruce Springsteen wore it like armour. Joe Strummer played it like a weapon. By fate rather than by design, it became the tool for the working musician. Unfiltered rhythm’s attitude and sound of sweat.

The Telecaster possesses some rigidity. You battle against it a little. Unlike a Strat, your hand does not encircle your neck. The bridge pickup is merciless. It’s bright, occasionally sharp, constantly candid. You cannot conceal behind it. That’s why players seeking clarity and cuts keep returning. It’s all cooked in: the twang, the snap, the coordinated chaos. Country, punk, reggae, indie, even jazz. The Telecaster flatters not at all. It requires.

Part of its mythology stems from what it did not alter. Although other designs changed with curves and humbuckers, the Telecaster mostly stood still. It ignored trends. It wasn’t seeking comfort. It maintained its plank-like form, its distinctive switch, its unapologetic bark. It was the Fender that never blinked. Its analogue integrity still resonates in a world of digital excess.

You find it on tiny stages as well as huge stadiums. On albums from dub records and country music. In Tokyo, Brixton, and Nashville. Not because it is classic but rather because it persists. Reissuing the Telecaster is unnecessary. It never left. It was constructed precisely the first time. And that rare feeling of permanence, in music or in life, is invaluable.

Loving the Telecaster is not to be nostalgic about it. One must embrace it on its own terms. Cruel, clearly spoken, defiant. Like a frank friend who never lies, a guitar that plays with you rather than for you. That, perhaps more than tone, ancestry, or nostalgia, is what makes it among the best instruments ever constructed.