The anthem of the middle class

It starts with a synthetic drone that mimics the buzz of fluorescent lights above a pile of microwave-ready dinners. Dry, nasal, constant like a monologue rehearsed in a mirror too many times, Jarvis Cocker slips in with that voice. He almost talks, meets the beat halfway, and lets the rhythm tell the tale of a girl wanting to be poor without the weight it entails. The synths pulse with inexpensive happiness, the kind seen in packed buses and chain restaurants.

Pulp had existed far before anybody noticed. Having seen enough clubs and missed enough trains, Jarvis knew the price of lying. After a chat with a Greek art student who said she wanted to live like the common people, somewhere in London, Jarvis wrote “Common People”. One sentence started the entire machine: stanzas loaded with chipped sarcasm, recollections of frozen dinners, and dancefloors filled with people unable to pay a cab home.

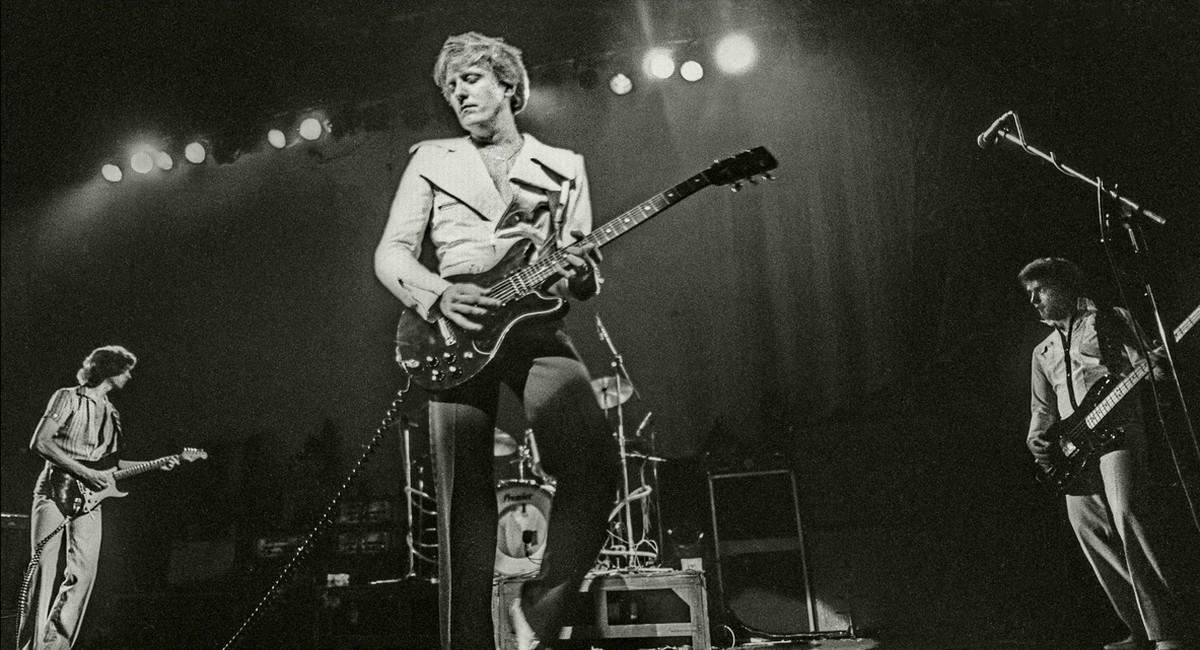

The song moves like a conveyor belt, relentless, robotic, and full of static. Steve Mackey’s bass plays low and steady, Candida Doyle’s keyboards spiral like a migraine, and the drums push forward with no intention of stopping. The framework never provides comfort. With every cycle it pushes harder. Like someone pointing at a wound and laughing without blinking, Cocker’s voice sharpens and becomes more caustic.

It built like a runaway train, and that was the mystery secret of the song.

(Mark Savage, BBC, 2025)

Common People arrived in 1995, smack in the center of Britpop, as the UK was donning nostalgia with fresh hairdos. Pulp did not elicit swagger or stadium cheers. They caused grief. With secrets, Jarvis seemed like a supply teacher and moved like he had read too much French theory and lit too many roll-ups. No gimmicks; only attitude and accuracy; his Top of the Pops performance burned itself into the group consciousness.

The track still adheres. You hear it in costly marketplaces attempting to mimic roughness. Between curated poverty and experienced fatigue, you feel it. The song asks for nothing in itself. It directs, it repeats, it plays once again. Jarvis did not need to shout. He merely reported the scene as it was: tiled walls, inexpensive beer, borrowed postures. And the beat went on.