Life in monochrome

Anton Corbijn’s Control unravels in subdued greys and cigarette smoke, draped in late 1970s England’s quiet weight. It doesn’t aim to exaggerate the myth of Ian Curtis. It stays rather in the gentle fall of a young man tied to words he could never entirely get free. The film follows a photographer’s eye, deliberate, still, sensitive to quiet. Reflecting a period when ambition conflicted with concrete and music became a lifeline for the disillusioned, each frame contains Macclesfield’s gloomy poetry on its streets and interiors. With a distant tenderness, the narrative follows the early growth of Joy Division, never pressuring emotion but rather letting it breathe.

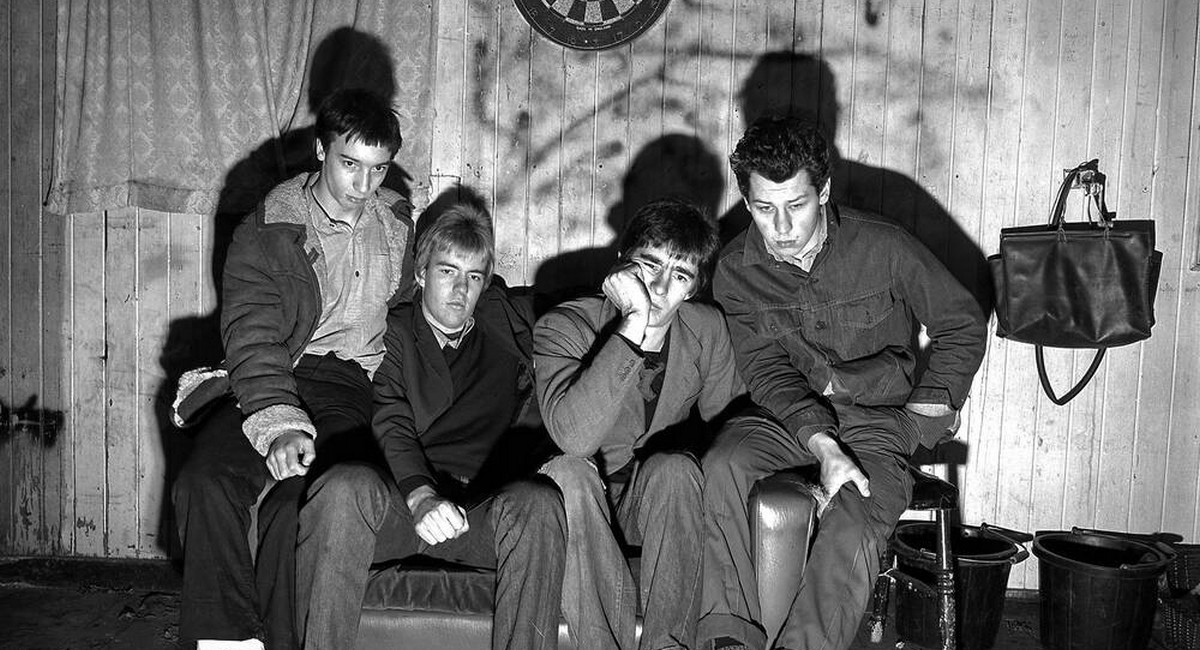

The shows’ palette of discipline will inspire their inspiration. Sam Riley channels rather than mimics Ian. Eyes half-closed, he slumps by a microphone; something unsaid trickles from his voice. Early band scenes are recorded as inadvert pulses, rehearsals in cold rooms, mistaken choices, subdued laughter in dark hallways, rather than as landmarks. Bringing Deborah Curtis’s story into clear and painful focus, Samantha Morton anchors the film in the domestic frailty that celebrity almost never approaches. Control discovers might in silence. A plate crashed on the ground, a baby sobbed, a bus window coated with mist.

Avoiding showmanship, the music scenes have an intimacy. “She’s Lost Control” reverberates across the screen with the strain of a body no more responding to itself. Filmed with a ghostly grace, never exploitative, always human are the epileptic seizures. Sharp basslines by Peter Hook and angled guitar by Bernard Sumner don’t burst into arena greatness. Tight quarters cause them to coil and twitches. When raised to a mirror of pain, the movie understands the songs possess an odd clarity. Like the music were being created in real time, Unknown Pleasures and Closer slips in quietly.

Some people visit the past for sentimental reasons and some people visit the past to understand the present better.

(Anton Corbijn, 2007)

Corbijn shot the movie in black and white; it never feels like a aesthetic option. It seems unavoidable. The monochrome preserves memories like dusty images stowed in drawers. It matches the loneliness that permeates the frame. A society where the future always seems somewhat out of reach. The cinematography mirrors the band’s look: restrained, severe, pulsating with something buried. Grand proclamations are absent as are mythologizing. Bodies breaking, voices trying to keep shape under fluorescent lights and tour schedules just days passing.

Control is not a eulogy. It’s a document of youth torn apart by intensity. It provides room for the things that went unsaid in songs that stated all. It lets the audience listen more than to be told by walking the line between realism and respect. With Ian’s last moments, the ending sequence provides no answers. Just quiet. And then silence. That of kind lingers long after the credits have died.