Drifting through lunar dreams

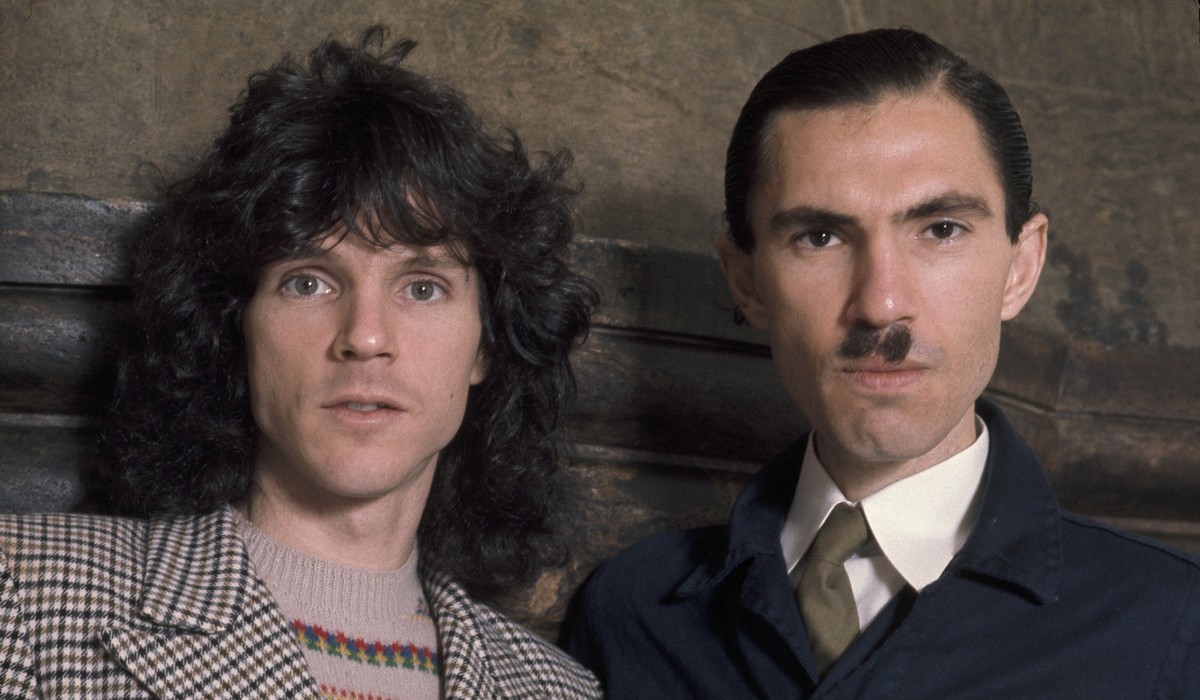

In early 1998, Moon Safari arrived like a soft signal from another world, unfolding its textures without hurry, inviting listeners into a sonic cocoon made of synths, Rhodes pianos and slow-filtered nostalgia. From the opening notes of “La Femme d’Argent”, there’s a sense of suspended time, a bassline that stretches like warm asphalt under the sun, and keys that shimmer with the precision of hand-cut crystal. Nicolas Godin and Jean-Benoît Dunckel, two friends from Versailles with backgrounds in architecture and classical music, sculpted these tracks in a small home studio, layering sounds the way others might stack colors or light.

Tracks like “Sexy Boy” and “Kelly Watch the Stars” offered a strange blend of melancholy and groove, as if Kraftwerk had stumbled upon a lost Serge Gainsbourg cassette. “Sexy Boy”, with its robotic vocals and fuzzy synths, became an unexpected anthem, carried by its video featuring a toy monkey floating through space. The band had never expected radio play, let alone MTV rotation. That surreal visibility, combined with the duo’s quiet presence, turned them into reluctant icons of a movement that had no name yet.

“All I Need”, sung by Beth Hirsch in a single take in a darkened studio, carries a raw intimacy, as if the mic had caught a thought mid-formation. Hirsch, an American living in Paris at the time, met the duo by chance through a neighbor. Her voice became a vessel for the album’s only fully human confession, hovering above gentle acoustic strums and analog drift. It is one of the album’s quiet anchors, grounding the dreamy synthscapes in flesh and breath.

“Ce Matin Là” introduces horns that feel lifted from a lost film score, perhaps Italian, perhaps French, perhaps imagined. Its lazy elegance evokes bicycles in early light, quiet conversations on café terraces, the weightlessness of days without plans. That sense of undefined time is one of Moon Safari‘s secrets – it avoids any sense of rush, offering music that seems to breathe, to stretch like morning limbs before the day begins.

Moon Safari is a superbly inventive album that creates a soundworld in your living room, a world where everything’s more shiny, chic and sophisticated than reality.

(Alexis Petridis, Mixmag, 1988)

At a time when most electronic music was aimed at the dancefloor or the club, Air crafted songs that sounded like they were written for empty rooms, balconies, open windows. Moon Safari helped shape the so-called French Touch, though Godin and Dunckel stood apart from their contemporaries in both sound and intent. Daft Punk brought the energy, Cassius the funk, but Air whispered to your headphones, to the moments between things. They worked with vintage gear not for fashion but for texture, obsessively dialing in the warmth of the past.

The album found its place in dorm rooms, art galleries, fashion shows, film soundtracks. Sofia Coppola heard Moon Safari and asked Air to score The Virgin Suicides. Their collaboration began with shared silence, then with chords passed back and forth, barely needing words. That film, like the album, floats between time periods, never fully anchored, always a little faded around the edges. Air’s music became shorthand for a mood – detached, romantic, tinged with longing.

“New Star in the Sky” drifts like a lullaby hummed by satellites, its melodies looping gently, endlessly. “Talisman” follows, ghostly and translucent, suggesting a presence more than a form. These tracks resist narrative – they create space rather than story, atmosphere rather than event. The sequencing of Moon Safari is part of its spell, each track melting into the next with no clear border, like thoughts trailing off before sleep.

Years later, musicians across genres still reference Moon Safari as a turning point, a permission slip to explore softness, texture, mood without drama. It gave electronic music a quieter voice, one that didn’t need to shout to be heard. Listening today, the album remains intact, untouched by trends, its light still diffused like dusk through curtains.